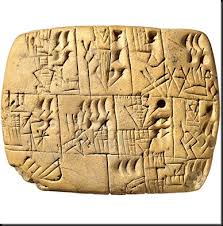

The answer to the first question is, nobody knows. It’s apparently a Sumerian invention, adapted by the Akkadians and picked up by all Middle Eastern cultures. The Phoenicians get credit for developing the first alphabet (22 letters), but it was really a mashup of Egyptian and Sumerian. The Hebrews weren’t far behind, and the Greeks invented vowels. Most of these cultures had some kind of origin story: writing as the gift of a god or demi-god. In the “Phaedrus” dialogue, Socrates tells of the god Theuth, who talked up his invention to the Pharaoh as an aid to wisdom and memory. The King was not impressed; he perceived the written word not as an aid but as a crutch:

By telling them many things without teaching them you will make them seem to know much, while for the most part they know nothing, and as men filled, not with wisdom but with the conceit of wisdom, they will be a burden to their fellows.

That’s a good description of pretentious windbaggery, and may be one reason why the Bible makes no mention of how writing was invented. Nobody writes anything in Genesis. In Exodus, there it is: Ten Commandments written by God himself and a Torah written by Moses (who was, after all, schooled in all the arts of a sophisticated culture). Written words are a medium for the Word, but not, strictly speaking, the Word Himself. (Remember, Jesus never wrote anything—recorded for us, that is—except some mysterious words in the sand.)

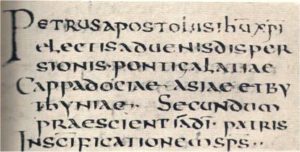

While the slow and tortuous development of writing went on, God spoke—to Noah, Abraham, Jacob, finally Moses. With the alphabet in place, he instructed prophets to set things down, not for their own erudition and proof-texting, but to let his people know what he was like. Like all technologies, writing is a double-edged sword, though more subtle than most: by it we pass down vital knowledge, and by it we’re burdened with conceited pedagogues.

Writing is a tool, not a talisman.

Of course God knows that. Knowledge is a means, not an end. Writing is a tool, not a talisman. It sets us free from immediate practical application and the limits of an individual mind, creates a place for the expression of ideas in a world of “things.” It also makes us think we know more than we actually do, when what it’s actually doing is setting the table for genuine knowledge. God doesn’t need it; his words endure even when no on

e listens to them. But our words are airy and fleeting. Like rain, they fall and evaporate on the heads of our hearers. Good words can bless, and evil words can hurt, but that depends on who hears them and what frame of mind they’re in.

Writing is our one shot at making our words endure past the hearing. But the Pharaoh’s words to Theuth—actually Socrates’ words—hold just as true today: reading and understanding the content represented by a pattern of words on a page makes us think we know the content. We don’t really know anything unless we live it out. That’s why the Bible puts such importance on doing: “Be doers of the word, and not hearers [or readers] only.” “He who hears my words and does them is like a man who built his house on a rock.”

Writing is a tremendous gift, no question. I make my living by it. Like all gifts, though, it’s not to be worshiped or exalted for its own sake, only for how it brings us closer to God.