But watch yourselves, lest your hearts be weighed down with dissipation and drunkenness and cares of this life, and that day come upon you suddenly like a trap . . .” And every day he was teaching in the temple, but at night he went out and lodged on the mount called Olivet. Luke 21:34, 37

As night spreads its dark wing, master and followers spread their blanket rolls on the Mount, where other Passover pilgrims have made their camps and built their cooking fires. The clamor of the city has ceased; only the occasional bleat or bray disturbs its majestic stillness.

Some of the disciples fall asleep immediately; others lay awake for a time, disturbed by the Master’s talk of earthquakes and celestial upheaval and being hauled before magistrate. Sleep stealthily overtakes them, though—except for one.

He lies awake, stomach churning, mind roiling. What has he got himself into?

In the beginning, I never questioned him. Who would? He spoke so beautifully, prayed so graciously—back then, he even smiled once in awhile. And the signs! And the healings! My own sister cured of a malignant growth on her neck, her life restored, better than ever. The day he looked at me and said, “Come.” The greatest day of my life, that. Wrapping up an extra cloak and pair of sandals, with a blessing and a kiss from Mother. I was off on a great adventure. Like stepping into a beautiful story—for all the heat and dust of those days.

What days: passing out neverending bread and fish on a hillside, feeling the raging sea fall flat at a single word, watching blind men see and lame men leap up from their pallets as the crowd shouts “Glory!” Going from place to place in advance of him, the children would run out to meet us and city elders give us an audience to proclaim in the center of town: “The Kingdom is at hand!”

I loved being his feet and voice those days; the wide-eyed little boys, the maidens blushing when they met my eyes, the prominent men—who used to barely spare me a glance—moving aside to give me their seat. We were going somewhere then. And when we entered Jerusalem, I thought we had arrived. I thought my heart would burst wide open.

But now, he seems determined to throw it all away. Why? What’s happening?

Thinking back, I see the signs. Those weird predictions about falling into the hands of evil men, and getting killed. Well, that’s coming clearer now: he’s asking to get killed. And they say the chief priests are looking for an excuse to do it. They won’t have to look long. The things he says, the claims he makes—outrageous, when you think about it. He talks like he’s the Blessed One himself. In the flesh! Will Yahweh stand for that? The healings have stopped; been months since we’ve seen one, or any other sign. Except for Lazarus, of course.* But that . . . I see how that could have been a trick. Staged. Only a few people need to be in on the plan—one last sign before entering Jerusalem.

But then there was that fig tree he blasted, right before our eyes.** Not like him. Not the kind of sign he usually performs. In fact, it looked like the work of a . . . darker power.

Remember what the Pharisees said, back in Galilee? “He casts out demons by the power of the Prince of demons”?

Could it be that—No, I’ll not believe it. He’s not a demon, but . . . it could be he’s being used by them. He told a story, something about a man cleansed of an evil spirit who becomes prey to seven other evil spirits . . .

He’s mad.

That’s the explanation; strange that in darkness the truth emerges plain as day. He’s lost his grip on reality; his mind has given way. Could there be any other explanation? Like King Saul, evil spirits have possessed him; he acts and speaks irrationally. He even said—I remember now—he said he would come back to life after three days! That must be why he staged that gaudy trick with Lazarus: three days in the tomb, and the man staggers out alive. But he wasn’t really dead—couldn’t have been; I see that now. But Jesus will be, if he keeps up this agitation. And he’s deluded himself that he won’t stay dead.

But he will. And . . .

So will the rest of us.

Oh.

Will we be accountable too?

Why not?

What’s to stop the temple police, once they’ve arrested the leader, to come for the followers? Yes, of course—they’d want to strangle the whole movement, nip it in the bud. Cut off the master, then go after the inner circle. Strike the shepherd, slaughter the sheep.

His skin turns clammy, as he lies under the pitiless, cold-eyed moon.

I’ve given you the signs, he says. Indeed. I see the signs, even if no one else does. It’s up to me to act. I’ve a widowed mother to think of, and sisters, not to mention myself. How will I make my way back, and what will I live on until I can get established back home? I must think this through, I must provide, I must . . .

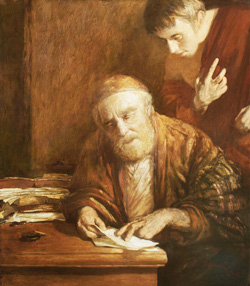

Judas turns his head. The Master is still awake, sitting up, his head bowed. Praying. He does that often; in fact Judas wonders if he ever slept more than an hour at a time, anywhere other than a boat in a raging storm (Madness—madness!) Look at me, Judas thinks. I loved you once; perhaps I love you still. You made my heart sing and my feet dance; you bent down to make me great. Was it all an illusion? Master—

Look at me.

But the Master’s head never turns, and his wakeful disciple can’t escape the impression that Jesus knows he is there, and even knows these tempestuous thoughts blowing through his mind. He has that way about him—the way of magicians and charlatans, of making you think they can see into your very soul.

But it’s a trick. It was all—all—a trick.

Silently, stealthily, with no announcement or fanfare, Satan steals into his heart.

*Only John records this miracle, but it was a significant factor in the chief priests and scribes deciding they could no longer wait to eliminate Jesus; see John 11:45-53 and 12:9-11.

.**Luke does not mention Jesus cursing the fig tree; Mark and Matthew do. Matthew records that the tree shriveled immediately after Jesus cursed it, while in Mark’s account the tree withered that same afternoon.

__________________________________________

For the original post in this series, go here.

Next>

Moses’ time expect the waters to drown them? Did the people of Sodom and Gomorrah look for fire from the sky? They were going about their lives, eating and drinking and making plans, when doom overtook them. The day is unexpected, and unavoidable. Judgment is certain and surgical—as sweeping as a scythe, and yet as precise as a needle. It will puck out or cut down, whether in a crowd of thousands or the dark and quiet of a bedroom.”

Moses’ time expect the waters to drown them? Did the people of Sodom and Gomorrah look for fire from the sky? They were going about their lives, eating and drinking and making plans, when doom overtook them. The day is unexpected, and unavoidable. Judgment is certain and surgical—as sweeping as a scythe, and yet as precise as a needle. It will puck out or cut down, whether in a crowd of thousands or the dark and quiet of a bedroom.”