Denouement is not a common word in everyday conversation, so for a long time I didn’t know how to pronounce it. It’s day-noo-MAHN (go easy on the final n). This is the resolution of the story, or (according to my dictionary), “the events following the climax of a drama or novel in which such a resolution takes place.” As we saw last week, the turning-point climax of THS arrives at the end of chapter 12, but the dramatic climax, which sees the defeat of Belbury, is yet to come. That defeat is not in doubt, though. It’s like the history of redemption: the denouement in which we’re living has plenty of drama, but the turning-point climax came with the Resurrection.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THEY HAVE PULLED DOWN DEEP HEAVEN ON THEIR HEADS

13-1 This may be the most difficult chapter of the whole novel for the contemporary reader. I had to skim over whole paragraphs the first time I read it, because of all the references I didn’t get. But there are also some interesting ideas that have affected my thinking. I’ve mentioned elsewhere that The Once and Future King was one of the formative books of my youth, and the lovable, backwards-living, eccentric figure of Merlin framed my conception of the Arthur legends. This Merlin is the polar opposite of of that one. But if there was such a person, I have no doubt he would be much closer to Lewis’s version: a creature of Celtic paganism and early Christianity, with ties to the old spirits of earth. He lived at a hinge in time, which Paul indicates in his message to the Athenians: “The times of ignorance God overlooked, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent . . .” (Acts 17:30, see also 14:16). Lewis, drawing from Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man, makes a distinction between “good paganism” and “bad paganism” in pre-Christian societies, the good leading eventually to Christ and the bad leading to demons. Merlin is of “good pagan” stock, and in fact a Christian—but very, very strange.

It’s interesting to compare his description of the moon with Filostrato’s in 8-3.

13-3 His accusation about Jane is disturbing to me. Can God’s plans really be thwarted by human will? We find ourselves at the intersection of destiny and choice, a question that has plagued philosophers, theologians, and even scientists since the beginning of time. In Perelandra, Ransom decides that God’s ultimate will can’t be thwarted, but he holds several paths in mind. If humans flub one plan, there will be another–but usually more difficult and with more painful consequences.

13-4 “Time is more important than we thought.” No kidding! Anyone who attempts to write serious historical novels must come up against the fact that the past is, if not utterly lost to us, then permanently out of reach. All our efforts to reconstruct it are tenuous at best, and if time-travel ever became practically possible we would soon learn how inadequate our efforts were. Dimble’s observation about “things always sharpening and coming to a point” is useful for all ages. He’s applying it to Merlin’s time, when a man could (supposedly) be semi-pagan and still justified, vs. the modern age, when people can no longer plead ignorance and must choose sides. But I think the statement has lots of applications: political, social, economical, spiritual. Vague principles come into sharper focus as a crisis approaches, and casual alliances no longer apply; people have to take sides.

13-5 Merlin learns that his pagan powers are no longer lawful (the image of his firelit face next to the bear’s–their earthy elemental kinship–is one of those literary pictures that will stick with me forever). As the inhabitants of St. Anne’s were profoundly discomfited by his presence, now Merlin learns how out of his element he is. The taint of corruption about him, due to his magic, is precisely what makes him useful to the cause. He is not totally sanctified. As Ransom says, “a tool (I must speak plainly) good enough to be so used, and not too good.” Upon learning his calling Merlin’s response is a bit like Christ’s, sweating drops of blood in the garden. Is there any alternative? Any other principality or power that can be called on to help? In the seventh paragraph from the end, notice his appeal to those who are not part of Christendom yet observe the “Law of Nature”—he’s talking about the Way, or the Tao, Lewis’s subject in Part Two of The Abolition of Man. But all earthly powers are to some degree under the sway of that Hideous Strength. Only powers beyond the earth can help now, and Merlin will contain them. Like an old wineskin filled with new wine, he will last only long enough to serve their purpose. And then he will lose his life, but save his soul.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: “REAL LIFE IS MEETING”

14-1 After almost a whole chapter devoted to St. Anne’s, we now go back to Belbury. Mark’s conversion at the end of ch. 12 was real–he has no desire to go back, though it’s to his advantage to play along. Frost’s dissertations in this chapter are easy to skim because he quotes people who were very consequential in Lewis’s day but almost unknown today. (Lewis had several arguments with Waddington, either in public correspondence or in footnotes.) However, the idea that “Existence is its own justification” carries on today in philosophers such as Richard Rorty and Peter Singer, and catchphrases like “Whatever is, is right.” Thomas Huxley, whom Frost quotes in the fourth paragraph, was an early defender of Darwinism who, contrary to Frost’s interpretation here, denied that evolution provided any ground for morals whatsoever. That didn’t stop his own grandson Julius (and subsequent deep thinkers) from trying to theorize morality from evolution. Frost represents the dead end of such attempts.

The paintings in the room where Mark begins his training range from the obviously perverse to the slightly “off”—which are more dangerous? Do you recognize any art styles? In the 12th paragraph from the end, he recalls reading of: “things of that extreme evil which seem innocent to the uninitiate . . .” Chesterton again, The Everlasting Man, ch.6. A pure heart and mind would be unaffected by these evil things (“to the pure all things are pure,” Titus 1:15), but Mark isn’t there yet. At least he recognizes the danger, and is soon delivered from it by a most unexpected circumstance.

14-2 Another difficult-but-rewarding section. If you have no patience with Lewis’s interplanetary mythology, okay, but notice that Jane still has her hang-ups and preconceptions that Mrs. Dimble is untroubled by (Titus 1:15 again?). Jane is not that different from present-day feminists who see sex as a power struggle; she may have some idea that her new “spirituality” has freed her from it, but the vision she sees in the Lodge says otherwise. The sensual woman in the flame-colored robe is easily understood as some sort of fertility goddess, but where do the dwarves fit in? Clearly, they’re all laughing at Jane, but further illumination will have to wait.

14-3 Tolstoy wrote a chapter of Anna Karenina from the POV of a dog—here’s a stream-of-consciousness from Mr. Bultitude. He, and all mammals, occupy a territory inaccessible to humans: pure quality, “a potent adjective floating in a nounless void . . .”

14-4 Mark has been having his own encounters with an earthy soul—a common tramp who shares certain characteristics with Merlin and others with Mr. Bultitude. Imagine how Mark would have reacted to him before his turning point in Chapter 12, and you can see some concrete effects of his altered attitude (it’s not quite a conversion—not yet).

14-5 Things are “sharpening and coming to a point” (as Dimble observes in 13-4) for Jane. She can’t exist in a spiritual vacuum for much longer; she’ll have to declare, either for Christ or for Ashtoreth. Which means necessarily that she will have to deal with her humanity, her place in the world. She’s been seeing herself as mostly a cerebral creature, a woman “without a chest,” made up of approved influences and pride and self-importance. Her conversation with the Director sets her up for “real meeting,” not just with God, but with her real self. Left to ourselves, we don’t know who we are; it’s impossible to disengage the true self from nature, nurture, and community. But God knows. Jane’s experience is hinted at in Colossians 3:3-4 and I John 3:2. Earlier her world was unmade; now she herself is remade by meeting the One who knows her fully. (Lewis was deeply impressed by Martin Buber’s I and Thou around the time he was writing That Hideous Strength. The title of this chapter comes from Part 1, sec. 13, where Buber writes, “All living is meeting.”)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: THE DESCENT OF THE GODS

The narrative will pick up and move faster from this point to the dramatic climax (at last! sighs the patient reader).

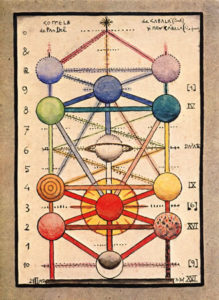

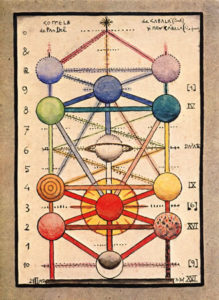

15-1 “The gods” of this chapter are not only the ruling spirits of our solar system (the “Fields of Arbol”), but pure qualities proceeding from our creator: Meaning, Charity, Valor, Age and Time, Festival Joy. Notice the “inconsolable wound” that wakes in Merlin at the approach of Venus: this is a stab of what Lewis calls “Joy” in his spiritual autobiography Surprised by Joy: the inborn longing that no earthly remedy can satisfy for long. Try listening to Holst’s The Planets before or during a reading of this section.

15-3 Both Frost and Wither are beginning to unravel. How?

15-4 In 14-5, Jane was told she would soon have to take a stand. This is the point where Mark will have to take a stand—his literal encounter with the cross. Note the “non-religiousness” of his conversion, which reflects Lewis’s account of his own conversion in Surprised by Joy.

15-6 Jules, the figurehead director of the N.I.C.E. who imagines he’s the real director, has been mentioned twice before; now he makes his appearance (remember the rule of three). He’s also a product of modern education, a character who might have been a decent-enough reporter or hack writer if he’d been brought up with traditional values. As it is, he’s mostly a fool.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: DINNER AT BELBURY

16-1 Recall Ransom’s observation to Jane in 14-5 that the demons hate their own minions as much as they hate us. This chapter will bear that out. The confusion of languages obviously recalls the Tower of Babel; the release of the animals suggests the Fall, when man and nature were set against each other. The plot to conquer nature has failed. Soon the earth itself will rebel . . .

16-3 – 16-6 Each of the Inner Ring meets a fate appropriate for him—how? Do they all get a chance to repent? When? Might Romans 1:14 have some relevance here?

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: VENUS AT ST. ANNE’S

17-2 The fashion show compliments 14-5 and the idea of our true selves being hidden: each woman has her dress picked out by the others; a dress that, once chosen, compliments qualities that they themselves didn’t fully appreciate. Why is the least said about Jane’s dress?

17-4 “Britain” vs. “Logres”: Lewis may get a little carried away here, with his idea of national “hauntings,” (any ideas as to what an American haunting would look like?), but the point is that humanity has had narrow escapes throughout history, some of them obvious and some not. There will always be a Logres, until Christ returns.

17-7 and 17-8 Mark and Jane are reunited. Recall that the novel began with their separation, and the narrative has pegged itself to their increasing distance. But there have been intriguing parallels throughout. They were each admitted to their respective Inner Rings in chapter 6. Jane was introduced to “the Head” of St. Anne’s, and Mark to “the Head” at Belbury, in chapter 7. Jane encounters the same holy fear at the beginning of ch. 11 that Mark encounters at the end. Jane’s true conversion in 14-5 is closely followed by Mark’s in 15-4.

Their final meeting involves a mutual descent: Jane coming down from her pretensions and Mark from his arrogance; she in her festival garments and he most likely naked. The world has been re-enchanted for them; they’ve rediscovered the magic of the commonplace. What happens next? A lot of baggage to work through, but remember Lewis called this “A modern fairy-tale for grownups.”

And so: “They lived happily ever after.”

Bible God is not like any other God. He’s the only ancient deity to link worship (temples, sacrifices, etc.) to a moral code. He is absolutely central; a person beyond personality, not a representative of window or fire, not an idea, not a philosophy. He escapes easy generalities, and so does his book.

Bible God is not like any other God. He’s the only ancient deity to link worship (temples, sacrifices, etc.) to a moral code. He is absolutely central; a person beyond personality, not a representative of window or fire, not an idea, not a philosophy. He escapes easy generalities, and so does his book.

Muslim groups who occupied the Holy Land and fought against the Crusaders. Poor Alcasan barely has the distinction of being a character in the story, and he’s not one now, as we’ll discover. These scenes with “the head” are the closest Lewis ever came to horror literature, but notice they are all experienced indirectly; narrated or mediated by a character rather than by direct action. He will take us into that forbidden chamber, but not yet.

Muslim groups who occupied the Holy Land and fought against the Crusaders. Poor Alcasan barely has the distinction of being a character in the story, and he’s not one now, as we’ll discover. These scenes with “the head” are the closest Lewis ever came to horror literature, but notice they are all experienced indirectly; narrated or mediated by a character rather than by direct action. He will take us into that forbidden chamber, but not yet.