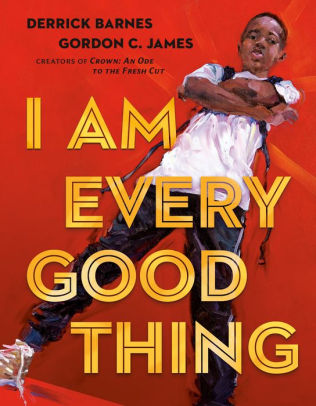

A picture book published last September is scoring stars in all the children’s-book review journals: I Am Every Good Thing. The book celebrates boyhood—particularly black boyhood—as a radiance of joy and exuberance and possibility.

Words and phrases like “good to the core,” “star-filled sky of solutions,” and “perfect” overstate the case. Other thoughts, like “I am the tree that falls in the forest and doesn’t make a sound” are more puzzling than clarifying. But the truly disturbing page, near the end, shows our hero with an unmistakable halo. “I am what I say I am” is the facing text.

I Am, or I Am Who I Am—Does that remind you of anyone?

I can understand the need for a book like this. Boys have been medicated and castigated and exhorted to act like girls for the last twenty years or so; about time they are appreciated for the rambunctious risk-takers they are. Black boys, especially, need inspiration to grow into strong and capable men.

But I’m not sure that the self-affirmation expressed in the title is the best way to go about it.

In fact, I’m sure it’s not.

You don’t have to be convicted of original sin to see the problem here. The title is patently untrue. Boys are not every good thing: while lively and funny, they can also be self-centered, aggressive, reckless, impetuous, and thoughtless. (My five-year-old grandson is a lot of good things, but I could tell you some stories . . .) Both boys and girls lack plenty of good things, like maturity and good judgment. That’s not a bug; it’s a feature, the very definition of a child.

Now, wait a minute, the author and illustrator might object: we don’t mean it literally. Or maybe they do. I don’t know, and the casual reader or first-grader who finds this book thrust at him by his reading specialist won’t know either. If the intention is the build his confidence, this reminds me of the self-esteem movement that began in the 1980s. I call it sticker-sheet confidence, because it seemed to consist of handing out accolades like exclamatory stickers (Awesome Work! You Rock!!)

The Self-esteem Movement, as a conscious Movement, was gradually buried under a pile of evidence that self-esteem is not endemic to good character. In fact, it may actually be inimical to good character. Building confidence is not a matter of telling kids they’re awesome, but helping them along the road to becoming awesome. That’s a lifelong process.

And they’ll never be as awesome as a halo-crowned figure identifying himself as I Am. Assuming godlike status is not the key to success. We have it on good authority that that’s the road to destruction.

What’s there to think about Isaac? A promised child, a near-victim, a weak husband, a gullible father . . . meh. He fades into the crack between Abraham and Jacob. and we see very little of his actions, even less of his inward thoughts. The defining moment of his life may well have been the instant when, somewhere around 15 years old, he lay bound on a stone altar gazing up at a knife held by his own father. Trustingly? Fearfully? Incredulously? Maybe all those things at once, and the experience could have scarred him for life. But now he enjoys an eternal existence as one-third of the patriarchal triumvirate, the “Abraham-Isaac-and-Jacob that the God of Israel would identify Himself by.

What’s there to think about Isaac? A promised child, a near-victim, a weak husband, a gullible father . . . meh. He fades into the crack between Abraham and Jacob. and we see very little of his actions, even less of his inward thoughts. The defining moment of his life may well have been the instant when, somewhere around 15 years old, he lay bound on a stone altar gazing up at a knife held by his own father. Trustingly? Fearfully? Incredulously? Maybe all those things at once, and the experience could have scarred him for life. But now he enjoys an eternal existence as one-third of the patriarchal triumvirate, the “Abraham-Isaac-and-Jacob that the God of Israel would identify Himself by.